Back in 1981, I was hired by the Santa Clara Valley Water District (today known as “Valley Water”) as a junior civil engineer to design pipelines. Soon after being hired, I found out that they were formed in 1929 by vote of as the Santa Clara Valley Water Conservation District and subsequent state legislation to manage the groundwater in the more populated north-central area of the county for a portion of the Santa Clara Valley.

The farmers and others voted to create a water district because over pumping (also known as “overdrafting”) of the groundwater basin due to agriculture had dropped the ground water level by about 80 feet in 1929. Several feet of permanent land subsidence and loss of groundwater basin storage capacity had also occurred by 1929. World War II brought dramatic industrial growth to Santa Clara County and an attendant growth in population, necessitating an increase in water supply and an increase in the reliability of that supply. It was recognized that sufficient water would be foundational to the economic prosperity of the county.

Since 1929, SCVWD has constructed and operated ten local reservoirs, many groundwater recharge ponds, almost 150 miles of pipe, and, as the growing need for water outstripped locally available sources, contracted for water supplies from the State Water Project and the Federal Central Valley Project. They have also constructed and continue to operate three water treatment plants to help shift urban water demands away from relying solely on groundwater. These measures, along with conservation and recycling, have stabilized the groundwater basins and reduced land subsidence in Santa Clara County. It’s worth noting that permanent land subsidence continued until about 1970, as did cycles of overdrafting. There is some aquifer compaction (subsidence) and expansion with changes in the groundwater basin, but it has been in the recoverable, elastic range for many decades.

More recently, since 1996 SCVWD has also entered into a groundwater banking and exchange program with the Semitropic Groundwater Storage District northwest of Bakersfield. While it does not increase the amount of the State Water Project annual contract allocation to SCVWD, it can make more of that allocation available in drought years. This allows SCVWD to use water from their banked amount at Semitropic provided there is sufficient pumping capacity ( physical and regulation based limitations apply) in the Delta and that Semitropic has sufficient allocation in the given year for SCVWD to take part of their Delta supply in lieu. This has helped limit drought impacts to the groundwater basins and reduce permanent land subsidence.

It took a long time and a substantial effort and amount of money, not to mention political will, to do all this. Looking at the current and rather expensive effort on the SCVWD Anderson Dam Seismic Retrofit Project, it’s never over.

Over a fairly long career in water resources civil engineering at SCVWD, I worked on many projects that contributed to the groundwater basins and the local water supplies in a number of ways, including large diameter pipelines, dam modifications, and flood management. Although my specialty is not groundwater, I learned more than a little bit about it, its importance, and its management. Here is what the SCVWD website says about groundwater, along with links to a number of topics and documents.

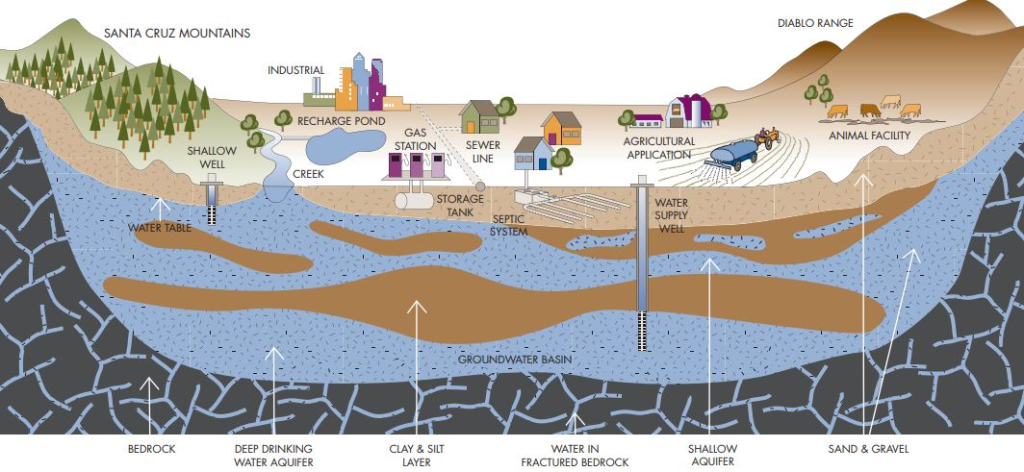

Here is a nice conceptual graphic of the groundwater basin in Santa Clara Valley from SCVWD.

At least in Santa Clara County, managed groundwater recharge occurs both through natural recharge in creeks and from constructed recharge ponds. Instream recharge from reservoir releases accounts for a large fraction of the managed recharge (over 50% in 2022). There is also natural recharge occurring from rainfall, creek seepage, and subsurface inflow. This graphic does leave out the dams/reservoirs and pipelines that enable SCVWD to move water around the county and serve both the treatment plants and the recharge ponds.

Conceptually, this and most other groundwater basins can be thought of as underground water storage reservoirs to which water is added and withdrawn.

It was clear to me that there were large parts of California and of the US where groundwater has not been managed effectively. In California, it has been treated as an extractive resource that could be pumped by any property owner (except in adjudicated basins). This could be done:

- Without much regard for anyone else, except for social pressure;

- Without regard for how much was pumped;

- Without regard for what the groundwater basin level was and how this impacted others in terms of increased pumping costs, less yield, or no yield if the level dropped below their wells;

- Without regard for land subsidence (which may occur over decades to centuries after groundwater levels have dropped) and resulting impacts on groundwater basin storage capacity capacity and expensive overlying infrastructure including roads, buildings, and sewer systems;

- Without regard for what pumping did to groundwater quality and impacts on moving contamination plumes; and

- Without regard for saltwater intrusion from nearby bays or the ocean.

I suspect this is like the situation in many other states, but I have not verified that in detail. This is very unlike the situation for surface water in California and the Western US, where the taking and use of surface water is heavily regulated and depends upon the establishment of water rights.

Until SGMA was passed, the only real option for dealing with these issues was to file a lawsuit and embark on an adjudication process. This could succeed, but it was expensive and very, very time consuming. There are twenty-nine areas of California, mostly in Southern California, where adjudication has occurred. This has not been an effective means of managing groundwater for sustainability on a statewide basis.

Back in early 2014, I signed up with an effort by Region 9 (California) of the American Society of Civil Engineers to lobby the state legislature for infrastructure and other efforts of concern to them. I had been retired for a few years, and I had time. I had spent most of my career on infrastructure and related issues, and I knew I could do that.

I met with my state legislators under this effort in May 2014, first with Assemblyman Stone and then with a staff member for Senator Monning. When I spoke to the Monning staffer, they expressed interest in several California water issues beyond what were in the ASCE talking points. I took off my ASCE hat and addressed them as “Dave Hook water resources civil engineer”. One of the issues I brought up was the need for improved groundwater management in California.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA)

A few months later, in early August 2014, I found out that a coalition of interested parties had been working on California groundwater legislation, and that it was planned to be introduced for consideration on August 4, 2014. I reached out to Senator Monning’s office to let them know I generally supported this, but that I had several specific comments on issues that I felt needed to be addressed. Here were my comments to them:

Senator Monning’s office thanked me for my comments, noting that they would be considered as the bills progressed. The three bills (AB 1739 [Dickinson], SB 1168 [Pavley], and SB 1319 [Pavley]) that are collectively called the “Sustainable Groundwater Management Act” were passed by the legislature after a fairly rapid legislative process and signed by Governor Jerry Brown on September 16, 2014. SGMA became law for California on January 15, 2015.

At long last, California had legislation that provided for comprehensive groundwater basin management. While I find this rather astounding, California was arguably the last state in the Union to formally regulate groundwater. I suspect this was due to the power of those who did not want their groundwater basins regulated or a subsequent loss of control. This included agriculture, municipal users, and others.

When I checked recently, I saw that the final legislation included the ability of the local groundwater management agencies to impose fees. It appears that my other two issues were addressed as well. I understand that I was not the only one with those concerns.

As noted on the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) webpage, Governor Brown said, “groundwater management in California is best accomplished locally”. Although the SGMA groundwater management will be overseen by DWR, local agencies are essential.

The DWR website summarizes what needs to be done:

SGMA requires local agencies to form groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) for the high and medium priority basins. GSAs develop and implement groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) to avoid undesirable results and mitigate overdraft within 20 years.

Although not noted above, GSAs can submit Alternatives to GSPs to achieve sustainability, as an alternative to a GSP. More on that below.

Although not stated explicitly above, it was certain that many GSAs would have to add (drill) additional monitoring wells and monitor them over time, or develop legal access to existing private wells. This would allow them to perform groundwater basin modeling (not required but a best practice), prepare the GSP, monitor the success or failure of their GSP over time, and to submit the annual reports required.

Although not really the subject of this article, there are “adjudicated” groundwater basins in California. These adjudicated basins have had a legal process to determine the groundwater rights of the pertinent parties. The adjudicated basins must submit a similar annual SGMA report to DWR. I suspect that basins adjudicated before SGMA became law are otherwise unaffected. I assume that judges overseeing adjudication after SGMA went into affect need to consider the SGMA principles, but I am not sure about this at all.

Almost Ten Years Later

With the tenth anniversary of the signing of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act coming up in September, I wanted to revisit what has been accomplished and what remains to be done.

First, as an interested and semi-expert bystander, I have been very impressed with the hard and thoughtful work DWR has done to execute their basic responsibilities under SGMA. I signed up to receive the regular SGMA emails, and they have communicated often and effectively. Per their web site, DWR needs to:

- Providing ongoing assistance to locals through the development of best management practices and guidance, planning assistance, technical assistance, and financial assistance.

- Providing regulatory oversight through the evaluation and assessment of GSPs.

I have seen every sign they are doing all of this.

DWR worked very hard on setting up the SGMA program after approval, with many tasks to carry out to hold up their end of things. This included identifying pertinent groundwater basins, formulating regulations, guidelines, advice documents, FAQs, performing outreach and education, setting up the SGMA portal online, and many other things. This took time.

Although not explicitly stated above, the first task required by others under the SGMA was “…Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) to form in the State’s high- and medium-priority basins and subbasins by June 30, 2017.” Per the DWR website, “Over 260 GSAs in over 140 basins” were formed by local action by that date. This required the submittal of a GSA formation notice to DWR.

It’s worth mentioning that a substantial part of the state did not have to do anything under SGMA, especially in areas with low-priority basins and subbasins, or where there is no recognized groundwater basin (mountains are a common example).

SGMA provides for local control and substantial flexibility in how Groundwater Sustainability Agencies are set up and in the extent of their coverage. This played out in very different ways in different parts of the state.

It’s clear that a fair number of GSA formation notices have been withdrawn, with 95 listed. While there could be several reasons for this, it does show that GSA formation and execution has not always worked out as local parties first hoped.

After the creation or identification of the Groundwater Sustainability Agencies, those agencies had to gather information including drilling monitoring wells where needed, model their groundwater basins (this seems essential to me, but it does not appear to me that the use of groundwater models is mandatory), and submit and obtain approval of their Groundwater Sustainability Plans. Deadlines for GSP submittal to DWR were January 31, 2020, for critically overdrafted basins and January 31, 2022 for high and medium priority basins. SGMA appropriately focused on faster action by the most critically overdrafted basins.

SGMA does allow GSAs to submit Alternatives to the GSP if it could be demonstrated to meet the SGMA objectives. The deadline for submittal for these Alternatives was January 1, 2017. This is before the GSA formation notice deadline, so I assume this was really an option for existing agencies that were functionally GSAs before SGMA passed.

On what “sustainable” meant, DWR noted in their Best Management Practices document:

…sustainable conditions within a basin are achieved when GSAs meet their sustainability goal and demonstrate the basin is being operated within its sustainable yield. Sustainable yield can only be reached if the basin is not experiencing undesirable results.

Originally defined in the SGMA section of the water code, the same BMP document from DWR gave guidance on what would constitute an “undesirable result”:

-

- Chronic lowering of groundwater levels indicating a significant and unreasonable depletion of supply if continued over the planning and implementation horizon. Overdraft during a period of drought is not sufficient to establish a chronic lowering of groundwater levels if extractions and groundwater recharge are managed as necessary to ensure that reductions in groundwater levels or storage during a period of drought are offset by increases in groundwater levels or storage during other periods.

- Significant and unreasonable reduction of groundwater storage.

- Significant and unreasonable seawater intrusion.

- Significant and unreasonable degraded water quality, including the migration of contaminant plumes that impair water supplies.

- Significant and unreasonable land subsidence that substantially interferes with surface land uses.

- Depletions of interconnected surface water that have significant and unreasonable adverse impacts on beneficial uses of the surface water.

DWR’s comments and approval or lack of approval of GSPs have certainly mentioned these criteria.

After submittal of the GSPs or the Alternative documents, the GSAs had to start submitting their annual report to DWR. Over time this would show how they were executing their plan.

Two Case Studies and a Few Examples

Case Study One – Santa Clara Valley Water District

At the relatively simple end of things, the Santa Clara Valley Water District as it now exists is a countywide special district dedicated to water resources management. It was created in 1929 and is the groundwater management agency for Santa Clara County.

According to staff, the SCVWD and the Association of State Water Agencies (ACWA) were both heavily involved in the effort to develop and pass the SGMA legislation. One of SCVWD’s key issues was the inclusion of the Alternative approach to GSP compliance – they did not want to have to start over, when they had been doing the same thing in a different format for a long time.

Without local conflict that I am aware of, SCVWD submitted GSA formation notices to DWR in June 2016 for two groundwater basins in Santa Clara County:

- Santa Clara Valley Water District GSA – Santa Clara

- Santa Clara Valley Water District GSA – Llagas Area

SCVWD had been managing the Santa Clara and Llagas Area basins for a long time, so this was expected.

In the process of thinking about this, SCVWD staff became aware of a modest portion of the North San Benito groundwater basin was located within Santa Clara County. They submitted a GSA formation notice to DWR in June 2017 for:

Santa Clara Valley Water District GSA – North San Benito

They collaborated with the adjacent GSA for the rest of the North San Benito Basin, the San Benito County Water District, on the preparation of the North San Benito GSP. The North San Benito GSP was approved by DWR in July 2023, with the SBCWD the lead agency for GSP preparation.

I confirmed with SCVWD staff that both the SCVWD’s groundwater well monitoring network and the groundwater model were adequate to the SGMA Alternative requirements.

Santa Clara Valley Water District had been preparing and executing Groundwater Management Plans for decades. Per the SCVWD website on Sustainable Groundwater Management, “In 2019, DWR approved Valley Water’s 2016 Groundwater Management Plan for the Santa Clara and Llagas Subbasins as an Alternative, determining it satisfies the objectives of SGMA”. This is a Groundwater Sustainability Plan equivalent acceptable to DWR; it was submitted in two parts, for the Santa Clara subbasin and the Llagas Area subbasin.

Staff did mention to me that SCVWD included a subject/requirement mapping summary in an appendix to the Alternative document to enable DWR to easily review compliance. Based upon my personal experience, this was an effective and even essential thing to do.

In 2021, SCVWD submitted a required update to their GSP Alternative. There was one public hearing and two notices in November 2021. It was posted with DWR for public comment between January and March 2022, with no public comments noted on the DWR website.

SCVWD has submitted annual reports to DWR as well, last in March 2024 for the October 2022-September 2023 period. The comments received back from DWR were interesting but not substantial, with one issue that should be addressed in future annual reporting:

The agency should incorporate similar details found in the calendar year-based annual report into the water year-based annual report submitted to the Department for SGMA compliance. The agency should provide details regarding performance against outcome measure (measurable objective) and outcome measure – lower threshold (minimum threshold) for each applicable sustainability indicator.

There is also mention that DWR is generally evaluating how things have been going with the submittal of these annual reports, with the possibility of different requirements in the future.

SCVWD does have to submit an SGMA Annual Report that is somewhat different than their yearly Annual Groundwater Report, see https://www.valleywater.org/your-water/groundwater. Among other things, SGMA requires a water year report, whereas SCVWD prefers a calendar year report. The SCVWD annual report also includes several categories of information not required by the SGMA Annual Report, including information on land subsidence and groundwater quality.

While much of what SCVWD staff have encountered in SGMA compliance was routine and very much like what they were already doing, there were some surprises.

- As noted above, they did need to address the North San Benito groundwater basin with the other GSA, SBCWD.

- The need to explicitly address the groundwater-surface water interactions did bring a better focus to that area for them.

- Addressing ecosystems as part of SGMA compliance also led to more consideration of ecosystems.

- SCVWD is a wholesaler of groundwater and treated water to 16 local retailers within Santa Clara County. SCVWD has traditionally influenced local groundwater use by retailers and others using price point signaling – i.e., the cost of water can go up or down depending upon whether groundwater use reductions are needed. This has worked for SCVWD, which has never explicitly attempted to regulate the quantity of groundwater used beyond this. SGMA does explicitly give GSAs the power to regulate the amount of pumping in a basin. The retailers who pump groundwater were quite concerned about how SCVWD’s potential future exercise of that power might play out. After substantial retailer/SCVWD discussion, a framework for such a future implementation of pumping regulation was adopted by the SCVWD Board of Directors on February 27, 2018, Item 5.1.

One final thought about SCVWD is that they have been dealing with the question of who pays how much for their groundwater (and treated water) for a long, long time. They have different and much lower groundwater rates for agriculture versus everything else. They have different geographic/basin zones which pay specifically for the projects and programs executed for their benefit. Sometimes the discussions about how much the various zones benefit from specific programs and projects and how much they should have to pay are extensive and challenging. This is not unlike what many GSAs have to deal with when a number of them are responsible for a single groundwater basin. At the same time, with one GSA (SCVWD) with a single seven member Board of Directors, I am sure it is more straightforward than basins with multiple GSAs.

Case Study Two – Paso Robles Groundwater Basin

I love wine tasting in the Paso Robles area of Central California. It’s my favorite in-state vacation destination for many reasons. I’ve known for a long time that wine growing can take a lot of water, and that groundwater is a critical issue for this area. Because of this and my interests in water, I have been paying attention to how SGMA compliance has played out in the Paso Robles area.

This has been a lot more complex and contentious than in Santa Clara County, with more stops, starts, and redirection. This does not surprise me. The original SCVWD agency was formed in 1929, on the third attempt to convince the voters a water district was a good idea. The current SCVWD is formed from five different agencies merged in various ways since 1929, with the first agency created to manage groundwater by those who felt it was important. It’s taken SCVWD 95 years to get to where it is today, and SCVWD has had a long history of doing things that bear a lot of resemblance to what SGMA requires. In contrast, SGMA requires something that is substantially brand new for the Paso Robles groundwater basin.

Before SGMA, the City of Paso Robles had implemented a moratorium in 2014 on new wells in the city due to a falling groundwater table. The people here certainly knew there was a very serious groundwater issue of overdrafting.

Another point which impacted the Paso Robles basin (and many others around the state needing GSAs, GSPs, and execution of those GSPs) is the relatively aggressive compliance schedule mandated by the SGMA. During the legislative process for the SGMA, there was a lot of discussion of whether the compliance dates were too aggressive, realistic, or not nearly aggressive enough. It was pointed out that the GSAs would have 20 years to achieve sustainability in the basin, which many felt was too long. I feel the compliance dates are rather reasonable and middle of the road, allowing for enough time while not having an indefinite deadline. However, they still require a lot of things to occur in a fairly short period of time for governmental actions that occur in a public fashion and are regulated by DWR and others.

The Paso Robles Groundwater Basin (Paso Basin) covers over 500,000 acres in Northern San Luis Obispo County and into Southern Monterey County. DWR determined that it was in “critical overdraft”, which they defined as “A basin is subject to critical overdraft when continuation of present water management practices would probably result in significant adverse overdraft-related environmental, social, or economic impacts.” This confirmed that the Paso Basin would need a GSA and GSP under DWR approval.

An attempt to form a water district to be the GSA for the Paso Basin failed badly in March 2016, with almost 80% of the voters against.

Subsequently, two areas within the basin decided to form water districts/GSAs, resulting in the Shandon-San Juan Water District GSA and the Estrella-El Pomar-Creston Water District GSA. This and subsequent actions have resulted in a number of other GSA agencies for the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin. Others include the San Miguel Community Service District GSA, the City of Paso Robles GSA, and the County of San Luis Obispo GSA.

For the coordination of all of these agencies and the preparation of one Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP) for the Paso Basin, a Paso Basin Cooperative Committee was formed by Memorandum of Understanding in 2017. This initial MOA included the Heritage Ranch Community Services District, the San Miguel Community Service District GSA, the City of Paso Robles GSA, County of San Luis Obispo GSA, and Shandon-San Juan Water District GSA.

The language in that MOA provided for dissolution of the Memorandum of Understanding after approval of the Paso Basin GSP by DWR. Subsequent to the original MOA, there have been changes:

- Heritage Ranch CSD is no longer part of the GSA MOA, as they had “requested removal on January 18, 2019, as DWR had approved their request to modify the basin boundary excluding the agency from the basin.”

- The MOA was amended by the parties on March 30, 2020, to remove the sunset clause.

- It appears that the Estrella-El Pomar-Creston Water District was approved as a GSA and has been added to the MOA.

It looks like work on the Paso Basin Groundwater Sustainability Plan began in 2016, with public meetings starting in 2017. I suspect it might have begun sooner, but I am not doing the research and calling people to find out. The 2020 Groundwater Sustainability Plan was submitted to DWR in January 2021. DWR’s January 2022 response letter said that the GSP was “incomplete”, noting:

The Department based its determination on recommendations from the Staff Report, included as an enclosure to the attached Statement of Findings, which describes that the Paso Robles Area Subbasin GSP does not satisfy the objectives of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) nor substantially comply with the GSP Regulations. The Staff Report also provides corrective actions which the Department recommends to address the identified deficiencies.

The attached Statement of Findings was quite explicit with these high level findings (I have not included all the subfindings):

A. The GSP has not defined sustainable management criteria in the manner required by SGMA and the GSP Regulations.

B. The GSAs do not sufficiently demonstrate that interconnected surface water or undesirable results related to depletions of interconnected surface water are not present and are not likely to occur in the Subbasin because the determination of non-applicability of the sustainability indicator is not supported with best available science.

A revised Paso Basin GSP was submitted to DWR on July 19, 2022. It was approved on June 20, 2023.

Annual Reports for the Paso Basin have been submitted for 2019 (in March 2020) through 2023 (in March 2024). The 2019 through 2022 Annual Reports are noted by DWR as “Submitted”, which I interpret as “We have it, we have reviewed it, it appears to show continued appropriate progress in complying with your GSP” for the Paso Basin. The 2023 Annual Report for the Paso Basin is noted by DWR as “Additional Information Requested”. The May 31, 2024 letter by DWR about the 2023 Paso Basin Annual Report to Blaine Reely, Paso Robles Area Subbasin Plan Manager, notes:

The annual report does not present groundwater elevation contour maps and change in groundwater storage for water year 2023 for the Alluvial Aquifer, which is the other principal aquifer in the Subbasin, citing insufficient data. Instead, the annual report presents groundwater elevation contour maps for the Alluvial Aquifer based on 2017 data. The annual report indicates that the GSAs have been working on expanding monitoring networks to address the data gaps. However, to date, groundwater elevation contour maps and change in groundwater storage information based on the current water year reporting period have not been provided for the Alluvial Aquifer and the annual report has not indicated when this information will become available. Failure to report on conditions from a principal aquifer makes it extremely difficult for the Department to determine whether the plan is being implemented in a manner that will likely achieve the sustainability goal.

The additional information required to be submitted in future annual reports includes the following:

1. Groundwater elevation contour maps for the Alluvial Aquifer illustrating, at a minimum, the seasonal high and seasonal low groundwater conditions, based on the water year reporting period.

2. Change in groundwater storage information for the Alluvial Aquifer.

Additionally, an action plan to address data gaps in the Alluvial Aquifer and a description of current groundwater conditions for each applicable sustainability indicator for the Alluvial Aquifer should be included in the upcoming periodic evaluation (required to be submitted by January 30, 2025).

I believe the GSP was prepared and approved with existing well information. In the June 20, 2023 Determination letter “Statement of Findings” that approved the GSP, it was stated that additional monitoring wells are needed. It’s not clear to me if any of those have been installed. I have seen a February 9, 2024 Request for Proposals for “Paso Robles Groundwater Basin Monitoring Well Network Expansion – Landowner Access Agreement Acquisition Support Services”. Reading that notice, the Paso Basin GSAs are hoping to use existing wells instead of drilling new wells to meet most if not all of their needs for more groundwater monitoring data. It’s good to see something addressing this issue, and I hope this is moving forward.

My interpretation is that DWR has decided they have waited long enough for up to date information on the Alluvial Aquifer, probably from more monitoring wells. This is a pretty clear discussion of what the Paso Basin GSAs must do, with a deadline. I suspect that this has come about after prior discussions and communications with the Paso Basin GSAs. I can only speculate that the lack of progress on this aspect of Paso Basin groundwater monitoring might be related to there being five GSAs and perhaps a disagreement over how to comply and who will pay.

I do see some continued controversy over how the management of the Paso Basin groundwater basin is moving forward. There was a June 23, 2023 San Luis Obispo County Grand Jury Report on it, “Can One Wet Year Wash Away the Paso Robles Basin’s Water Worries?” The Paso Basin Cooperative Committee did consider responses. While I have not found the final responses, it appears that they agreed with a number of the comments.

I believe the situation in the Paso Robles Basin is somewhat typical for many areas in the state. Groundwater is a very major part of the water supply locally. The groundwater basin has been overdrafted for a long time, with many needing to drill new wells. The locals had to form GSAs to address this by first submitting a GSP and then annual reports showing how they are performing versus the plan. There are definite local concerns about how the groundwater basin can reach sustainability and with the cost and equity of who pays for what and who is impacted with how much water they can use. There will be local impacts to agriculture and the economy.

The Big Picture After Almost Ten Years

The good news is that there are 73 California groundwater basins with an approved GSP. As mentioned above for SCVWD, there are also basins where DWR has accepted or is in the process of reviewing an Alternative to a GSP. There are nine Alternative approved by DWR.

This means that there are 82 basins where one or more GSAs got together and reached agreement on what to do, obtained approval from DWR, and have hopefully started doing that. That is over half of the “over 140” groundwater basins noted by DWR as needing a GSP or equivalent. Adding the 29 “adjudicated” basins where SGMA reporting is the only requirement, that is 111 of over 140 where a plan is in place and hopefully being executed adequately. Although the proof is in the pudding for how execution of these GSPs work out, this is great in less than ten years.

There are areas of California that are still without an approved GSP. Looking at the DWR portal, there are:

- 23 GSPs noted as status “Inadequate” by DWR.

- 11 GSPs noted as “Review in progress” by DWR.

- Two Alternative proposals noted as “Review in progress” by DWR.

Among the GSP noted as “Inadequate”, there are six “Basins Deemed Inadequate and Potentially Subject to State Intervention” by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). Clearly, “Inadequate” does not necessarily lead to state intervention.

- Delta-Mendota Subbasin

- Chowchilla Subbasin

- Tulare Lake Subbasin

- Kaweah Subbasin

- Tule Subbasin

- Kern County Subbasin

The Tulare Lake groundwater basin, with a GSP deemed inadequate, is the first California groundwater basin that has been placed on “probation” status by the SWRCB in April 2024, leading to a loss of local control and fees imposed. This is playing out with a conflict with the agricultural economy and the local groundwater sustainability. The initial steps required by the SWRCB include groundwater pumpers recording and reporting how much groundwater is pumped and the payment of fees. If the deficiencies in the GSP are not addressed within a year, the SWRCB could move into the “interim plan” stage which could include a public hearing and pumping restrictions or fines for exceeding water allotments.

The stated reasons for the “probation” status and active intervention in the Tulare Lake subbasin by the SWRCB includes these deficiencies as noted in the San Francisco Chronicle on April 12. 2024:

The plan allows groundwater levels to continue dropping, in many areas to well beneath historic lows; hundreds of domestic wells, many in disadvantaged farmworker communities, would likely go dry under the plan; and threats to infrastructure from land subsidence are not clearly identified.

I understand that politics and struggles over control are in play in the Tulare Lake subbasin. There are five GSAs jointly responsible for the GSP and execution of the currently inadequate plan, which could be a factor. From the communications available, the SWRCB and DWR are hoping that Tulare Lake will address the inadequate issues and regain local control.

I found out on June 12, 2024 of the “…State Water Board’s upcoming hearing for the consideration of a Probationary Designation for the Kaweah Subbasin.” This hearing is scheduled for November 5, 2024, after two late June 2024 public workshops on the subject.

Upon checking the SWRCB Groundwater Basin’s page, I find that there is an upcoming Probationary Hearing for the Tule Basin on September 17, 2024. The deadline for written comments has passed, and the public workshops were in April 2024.

Given the number of other basins with either an inadequate GSP or one that is still “Review in progress”, I suspect there will be more with state intervention and “probation” status. I hope that some of those in “inadequate” or “potentially subject to state intervention” status will observe the result at Tulare and process at Kaweah and redouble their efforts to avoid probation and loss of control. I am sure the SWRCB and DWR hope the same thing.

It’s also interesting to see that SWRCB also lists “Groundwater basins with Unmanaged Areas“, noting that these can lead to intervention. To me, this means that there are high- or medium-priority basins or subbasins where no GSA stepped up to manage all or part of it. There is one “basin with unmanaged areas under state intervention”, The Upper San Luis Rey Valley Subbasin. Looking at the communications on the SWRCB website, it’s clear that reporting of groundwater use is required and fees are being billed to the groundwater users in the area.

Now that we are almost ten years into the SGMA, the future continues to come into focus on California groundwater use. If GSPs or Alternative plans or their execution do not yield sustainable groundwater use over time in basins, there will be additional local impacts such as metering and reporting, payment, and even limitations on groundwater use. This will change land use in some areas, or the kinds of activities that can be carried out due to cost of sustainable water.

The law and SGMA

As is perhaps inevitable in America with new state laws that definitely move the cheese for people and corporate entities used to pumping as much water as they feel like without consequences, there are also a number of lawsuits in process which could affect the SGMA.

One of them is Mojave Pistachio, LLC et al. v. Superior Court of Orange County, Indian Wells Valley Groundwater Authority (Case No. G062327, opinion published Feb. 8, 2024). Mojave Pistachio, LLC sued Indian Wells Valley Groundwater Authority, contending that “IWVGA’s groundwater sustainability plan illegally deprived Mojave of its vested rights to pump groundwater from the Basin by conditioning Mojave’s continued use of groundwater on payment of the replenishment fee.” The appellate court ruled narrowly that the “pay first” rule applies here, concluding that Mojave Pistachio, LLC could not successfully challenge the fee until after paying it. This has clearly left the door open to further challenges after payment, with no clue to me on how it might or might not succeed. This lawsuit, if refiled after payment, would be back to address the basic tenet of the SGMA that the GSAs have a right to payment for the groundwater extracted within the basin. In my humble opinion, this is is a rather existential question for the SGMA.

Another case is California Sportfishing Protection Alliance v. Eastern San Joaquin Groundwater Authority et al., Superior Court of Stanislaus County Case No. CV-20-001720. This is still in court. The lawsuit filing noted this:

Cause of Action

(Violations of SGMA)

37. Defendants did not follow the procedures required by SGMA before adopting the GSP, and the GSP violates the substantive requirements of SGMA in that:

a. The GSP does not achieve sustainable groundwater management, meaning “the management and use of groundwater in a manner that can be maintained during the planning and implementation horizon without causing undesirable results.”

b. The GSP is not likely to achieve the sustainability goal established by the GSP within 20 years.

c. The assumptions, criteria, findings, and objectives, including the sustainability goal, undesirable results, minimum thresholds, measurable objectives, and interim milestones are not supported by the best available information and best available science.

d. The GSP does not identify reasonable measures and schedules to eliminate data gaps.

e. The sustainable management criteria and projects and management actions are not commensurate with the level of understanding of the basin setting, based on the level of uncertainty, as reflected in the Plan.

f. The interests of the beneficial uses and users of groundwater in the basin, and the land uses and property interests potentially affected by the use of groundwater in the basin, were not adequately considered.

g. The GSP does not substantiate its findings that the projects and management actions identified in the GSP are feasible and likely to prevent undesirable results and ensure that the basin is operated within its sustainable yield.

h. The Plan does not adequately supports its findings regarding potential overdraft conditions.

i. Defendants have not adequately responded to comments that raise credible technical or policy issues with the Plan.

j. Defendants did not adequately engage the public in planning and adopting the GSP.

That is quite a list of defects alleged in the GSP and the process to produce it. While I think this is interesting and certainly matters to anyone doing a GSP, this does not seem like an existential threat to the whole SGMA structure to me. It’s not clear to me what the status of this lawsuit is; in January 2024, there were a number of closed session items listed on governing body agendas for many of the defendant GSAs. One online source lists a tentative ruling, but I was not able to determine what that ruling was.

I am certain there are a number of legal actions relating to the SGMA that I have not found yet.

There is a useful piece by Tara E. Paul, Senior Counsel at Allen Matkins on “SGMA at 10 Years: Navigating California’s Groundwater Future“, 05/23/2024. I think the author’s opinion on the legal situation regarding the SGMA is fair:

It is a central tenant in SGMA’s provisions that it cannot be implemented in a manner that harms existing groundwater rights. Nevertheless, groundwater users have worried since the Act passed that it would result in such harm. Unsurprisingly, as GSAs finalized and submitted for review or began implementing their GSPs, litigation followed. Landowners in several counties in the Central Valley, Central Coast, and eastern desert regions are challenging the management tools the GSAs are utilizing on the grounds that the tools unlawfully interfere with their water rights to groundwater. Disputes have erupted over volume limitations, priority to sustainable yield, and fees imposed on acreage and water extraction volumes. In some instances, plaintiffs are asking the courts to conduct a comprehensive adjudication of all water rights in the basin area and to impose a physical solution to timely reach mandated sustainable yield goals in order to displace the tools or approach chosen by a GSA.

As these cases make their way through the courts, the decisions will help delineate the extent of a GSAs’ authority to regulate groundwater use under SGMA. There are likely to be more challenges to GSP implementation, modifications to GSPs as groundwater conditions change, and possibly a new role for the State Water Board in regulating basins that fail to comply with SGMA mandates.

Other Perspectives on SGMA Almost Ten Years In

I’m sure there will be more written on this subject, especially in the news media. However, here are some other thoughts to date as we approach ten years of SGMA.

The Successes, Shortfalls, and Next Steps for SGMA – Dudek, by Dudek Hydrogeologist Jill Weinberger.

Spotlight April 2024: Members Share Thoughts on SGMA …, by the Association of California Water Agencies.

AG ALERT: 2024 marks a decade of SGMA regulations, by the California Farm Bureau.

Many obstacles remain in SGMA implementation, by Farm Progress.

DWR Celebrates the Hidden Water Resource Beneath Our Feet, by DWR, which also reflects on the upcoming tenth anniversary of SGMA.

Calif. marks 10 years of groundwater sustainability, by Christine Souza, The Sun-Gazette Newspaper, Exeter, California (north of Bakersfield, east of Coalinga).

Leave a comment